The Library of Babel is an email newsletter exploring the wonders of literature, history and magic. All the installments are free. Sign up here:

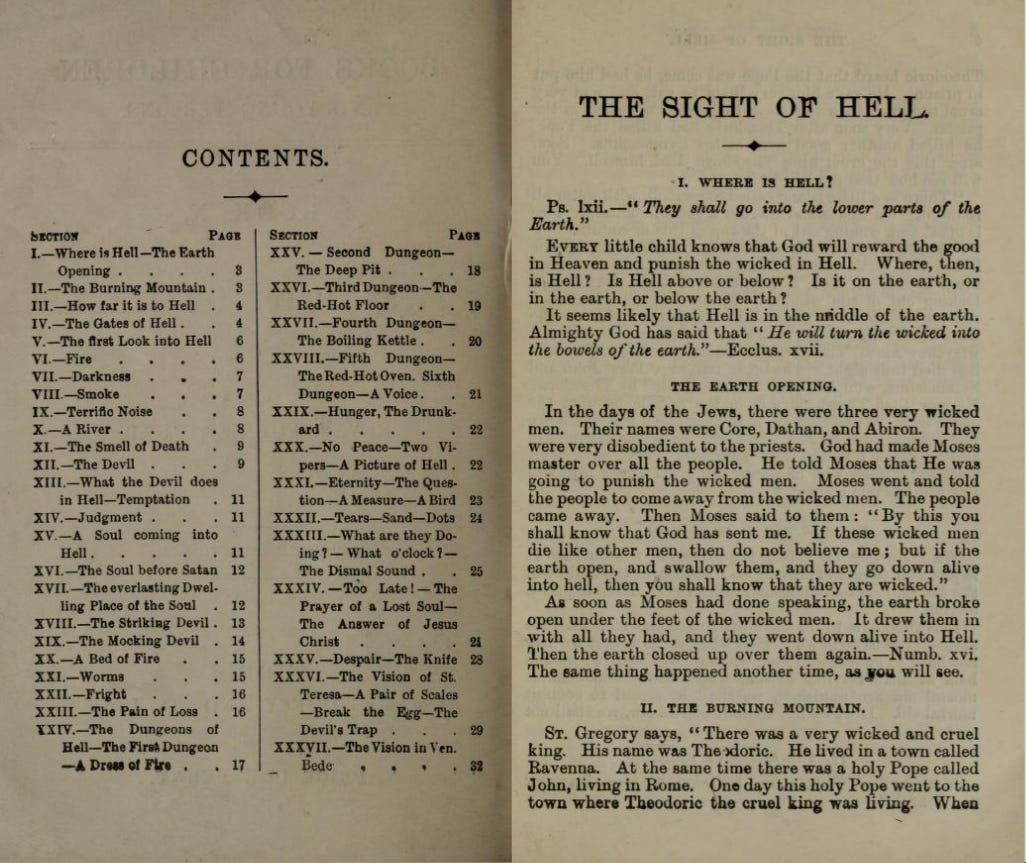

In 1861, a Catholic priest named John Furniss did what he believed to be the most sensible thing a man of God could do. Furniss, an educator with extensive experience in organizing Christian camps for children in England, wrote the first religious tract about Hell specifically dedicated to "children and young persons." The name he gave to that pioneering work? The Sight of Hell.

Looking back at such a trailblazing endeavor, we might be appalled by its very premise. Understandably, this is how most critics today treat the text. Contemporary reviewers of The Sight of Hell, however, had other things to say about it—some, like the Daily record (April 24, 1872), even used words like "pleasant" to describe the book.

Now, as a self-described modern, non-religious Jewish man, I fall into the former camp. And yet, when I read this short work, I couldn't help but notice that The Sight of Hell is actually written in a clear, almost charming way. The tone of the book is down-to-earth, simple to follow, and—because of its gory subject matter—deeply unsettling. Which was probably the point.

In his brief work, 32 pages in total, Furniss does not attempt to explain death and its finality to his readers—arguably the most baffling subject for a child. Instead, he describes, with unimaginable vividness and in visceral terms, the torments awaiting all the children who misbehaved in life. Yes, children. His Hell is populated with children and the devils that torment them.

The book opens with a seemingly reasonable, almost scientific question: "Where is Hell?" I've quoted the entire section here to give a sense of the language:

Every little child knows that God will reward the good in Heaven and punish the wicked in Hell. Where, then, is Hell? Is Hell above or below? Is it on earth, or in the earth, or below the earth?

It seems likely that Hell is in the middle of the earth. Almighty God has said that 'He will turn the wicked into the bowels of the earth.’

With that question settled, our descent into Hell begins. A major justification for this journey follows the advice of St. Augustine—to reach Hell before we die so that we might change our ways and avoid eternal damnation. From this point on, the book becomes an exercise in guided imagination, where Furniss instructs us to picture what we will encounter.

The first major sight, after walking for miles through darkness, is the gates of Hell, where the words "This is Hell, where there is neither rest, nor consolation, nor hope." are written in letters of fire.

Do you hear that growling thunder rolling from one end of Hell to the other? The Gates of Hell are now opening.

Inside Hell, past the gates, awaits the sinner a sight so terrible that it "cannot be told." The sheer size of Hell is immense. Traditional accounts of Hell speak of nine circles; Furniss knows only three: upper, middle, and lower Hell. The deeper one goes, the worse the torments, with the lower Hell being a place where "the torments are beyond all understanding."

Now that you're there, Furniss instructs his readers: "Look at the floor of Hell. It is red-hot, like red-hot iron." The walls are made of enormous stones, from which sparks of fire "are always falling."

Furniss' Hell is one of fire and brimstone. Its rain is made out of fire. And yet, despite all the flames and heat, it is also an abyss of total darkness.

The fire of Hell burns, but gives no light… No stray sunbeam, no wandering ray of starlight ever creeps into the darkness of Hell.

This darkness is so absolute that it redefines our understanding of darkness itself. The dark places we know in our world are, according to Furniss, mere glimpses of the true darkness to come. Since Hell exists as an objective reality, it becomes, in Furniss' worldview, the Platonic ideal of everything that is bad, evil, and painful in life. And yet, because Hell is literally the worst place imaginable, even this Platonic ideal can be surpassed. The total darkness, in which no light can ever shine, is made even worse by the suffocating smoke that has filled Hell for nearly six thousand years.

Oh, and there's also a terrible noise ("Terrific Noise"). And a river made of an endless stream of tears. The stench of death is unbearable. And Satan judges every soul with no mercy. And don't forget the worms, the beds of fire, the screams and how no matter what you did in life to get to Hell, everyone in the end burns forever.

Reading Furniss' short work, which was just one of many other works he wrote for children, I couldn't help but think of another literary descent into Hell—that of Dante Alighieri in The Divine Comedy. Inferno is the most elaborate vision of the Christian Hell in all of Western literature. Furniss’ work does not contain as many details as Dante’s, nor does it need to. What it lacks, in contrast to Dante’s magnificent poem, is something else entirely.

In Inferno, every punishment fits the crime (or sin), and the narrator gradually gains knowledge and understanding of divine justice. In some of the most moving scenes, Dante’s character even finds himself questioning certain punishments—challenging, if only briefly, God’s ultimate justice.

Furniss, on the other hand, is purely didactic. He leaves no room for doubt or questioning. And why should he? Those who question things do not get a happy ending, remember? While this may be sound theological reasoning—and despite Dante's own doubts, God has the final word in Inferno as well—Furniss' work is ultimately not a particularly interesting one, except as a historical document.

On that account, however, it is fascinating. It forces us to consider what people once taught children (and adults, of course) to make them behave.

It might be too simplistic to conclude that sensibilities in the 19th century were vastly different from today. But let us not forget that The Passion of the Christ aired in 2004, and many, many parents reported taking their children to see that body horror.

Fascinating subject. Thank you for you insight into this unusual document.

sorry, but it reminded me so:

""No sight so sad as that of a naughty child," he began, "especially a naughty little girl. Do you know where the wicked go after death?"

"They go to hell," was my ready and orthodox answer.

"And what is hell? Can you tell me that?"

"A pit full of fire."

"And should you like to fall into that pit, and to be burning there for ever?"

"No, sir."

"What must you do to avoid it?"

I deliberated a moment; my answer, when it did come, was objectionable: "I must keep in good health, and not die."

"How can you keep in good health? Children younger than you die daily. I buried a little child of five years old only a day or two since, — a good little child, whose soul is now in heaven. It is to be feared the same could not be said of you were you to be called hence."

Not being in a condition to remove his doubt, I only cast my eyes down on the two large feet planted on the rug, and sighed, wishing myself far enough away.

"I hope that sigh is from the heart, and that you repent of ever having been the occasion of discomfort to your excellent benefactress."

*********

"And the Psalms? I hope you like them?"

"No, sir."

"No? oh, shocking! I have a little boy, younger than you, who knows six Psalms by heart: and when you ask him which he would rather have, a gingerbread-nut to eat or a verse of a Psalm to learn, he says: 'Oh! the verse of a Psalm! angels sing Psalms;' says he, 'I wish to be a little angel here below;' he then gets two nuts in recompense for his infant piety."