Apologies to all you Francophiles, but the English executed their king first

The Free Monarchy and the Divine Right of Kings in the Trial of King Charles I

The Library of Babel is an email newsletter exploring the wonders of literature, history and magic. All the installments are free. Sign up here:

Before today’s essay about the trial and execution of king Charles I - which was so so fun to work on by the way - I wish to share with you a wonderful conversation I had with Ricky Lee Grove at The Paperback Show. We talked about Tolkien and his essay about Fairy-stories. You can listen to our talk here.

And now for the main course: The Free Monarchy and the Divine Right of Kings in the Trial of King Charles I.

On January 20, 1649, the trial of Charles I began. The charges the King of England faced was of treason against the English people. After more than two and a half years in the hands of Parliament, the king was forcibly transferred in the last two months of his life to the custody of the army, which demanded revenge for the loss of lives and the destruction that the king had brought upon his people. Seven years of civil war had led to dozens of attempts at compromise by all of the king's opponents, but none of these efforts made the slightest crack in Charles's conviction about the justice of his cause. Thus, every offer, no matter how tempting or conciliatory, was rejected by him as he sought time for the royalist camp to recover from defeats on the battlefield.

It was logical, then, that when the king first heard of the decision to put him on trial, he dismissed it with scorn, assuming it was yet another, albeit aggressive, attempt to frighten him into relinquishing his absolute powers and handing them over to Parliament. A week before the trial, when the king was rushed in a carriage surrounded by armed guards to the capital, he briefly met with Colonel Thomas Harrison, the most fanatical and anti-monarchist subordinate of Oliver Cromwell, the unofficial commander of the army. When Charles suggested that his death would come at the hands of a secret assassin from the army, Harrison smiled with satisfaction and reassured the king. The army would not harm him through a covert plot, Harrison explained, "but everything it does will be visible to the world."

And indeed, after the army's purge of Parliament last December—a purge that included suspending the House of Lords and expelling all moderate opposition to the king from the House of Commons—the final step toward carrying out divine justice on this 'man of blood' (as the army called Charles) was set in motion.

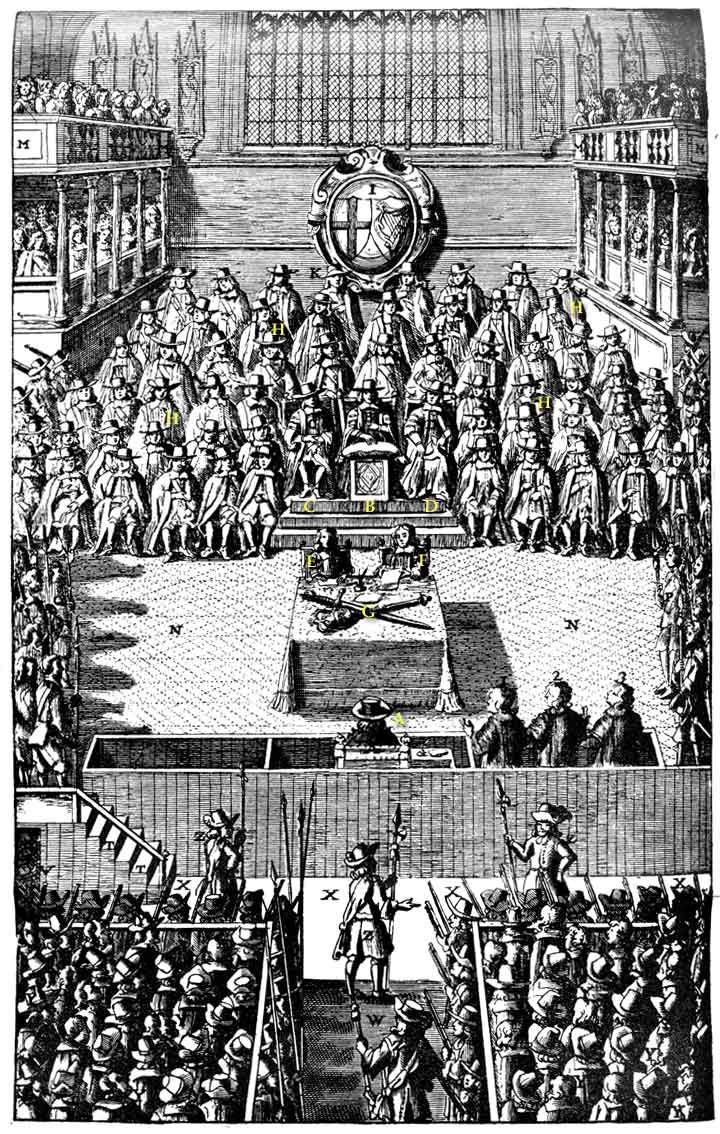

However, the appearance of legal process was necessary to proceed down such a radical path. The High Court of Justice, established to try the king, was created for the first time in English history not in the name of the king, but in the name and authority of the people. According to a royalist joke circulating at the time, this move prevented the embarrassment of signing Charles I's death warrant in the name of Charles I. Every step of the army's and the purged Parliament's actions was carefully planned to create the appearance of legitimacy for the trial of a sitting king, a precedent that had no historical parallel—a point that the king raised several times during his trial.

It took the House of Commons sixteen days of deliberations to draft a suitable indictment. This was because English law up until that time had defined treason as an act against one of the king's two bodies: his physical body or his political body—meaning an attack on his ability to rule the kingdom, which was identified with his person. To put Charles I on trial, the purged House of Commons adopted an entirely new theory of English monarchy—a theory that claimed the political body did not reside in the king’s physical body, but in the people.

Once the indictment was drafted, the political theater prepared for the king's trial was sharpened and rehearsed by the panel of judges and the court president, John Bradshaw. The problem, much to the prosecutors’ frustration, was that the show revolved around a hostile participant who was happy to shatter the illusion of the legal framework on which the trial was based.

That participant, Charles Stuart, still the King of England, was brought before the court on the first day and sat in the defendant's chair. His appearance surprised those present; dressed in black, the king displayed his hair and beard, grown wild, as he had not allowed anyone near him with a sharp blade since the army had dismissed his royal barber. While waiting for the trial to begin, he calmly and indifferently scanned his prosecutors and found that he knew only a handful of them.

John Cook, the prosecutor in the trial, was asked to read the brief indictment. The main accusation in the indictment was that Charles, as King of England, had been granted limited power to govern in accordance with the laws of the kingdom, but through his actions, the king had revealed his malicious plan to grant himself tyrannical and unlimited power and to rule England according to his own will. Through a treacherous and evil campaign, the king had sought to abolish the rights and freedoms of the people. "In the name of the people," Cook concluded the indictment, "Charles Stuart is declared a tyrant, traitor, and murderer—an open and implied enemy of the English Commonwealth." The king, who had remained indifferent during the reading of the indictment, burst out laughing when he heard himself declared an enemy of the peace. His peace.

The indictment aimed directly at the constitutional crisis that England faced due to Charles's complete identification with the new Baroque ideal of the divine right of kings. Indeed, the English political system had experienced difficulties arising from changing times and shifting power dynamics within the kingdom in the past thousand years. Yet, while for centuries there had been tension between two deeply rooted traditions in the kingdom—two traditions that were perceived as complementing one another—these traditions were ultimately torn apart by the intrusion of the Baroque doctrine of the divine right of the king. This doctrine exposed the inherent contradictions in the English constitution under a careless king like Charles I.

The traditional English view until the Baroque period depicted the English kingdom as a political body, with the king identified as the head. According to this monarchical logic, a political body without a head was a distorted and unnatural body. Thus, while Renaissance thinkers in Italy argued that if a person wished to live in a free state, they must live in a free state (i.e, a republic - the ideal form of governance for liberty), England’s monarchy was praised as a "free monarchy." This term was not an empty propagandistic expression but stemmed from the unique status of England during an era of centralized monarchy and church, which characterized Baroque Europe on the continent. England's uniqueness derived from the political system's consensus in accepting two political principles that, in practice and in perception, limited the monarchy.

The first principle was the distinction between a king and a tyrant, a distinction drawn from the political thought of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. An English variation of this distinction is found in Thomas Smith’s De Republica Anglorum (first published in 1583):

"The law, they define (referring to the English), as the institution of the king, who by inheritance or election comes by the good will of the people to that government and leads the commonwealth according to its laws, seeking the good of the people no less than his own. A tyrant, they call one who by force attains monarchy—against the will of the people, violates established laws for his own pleasure, enacts new ones without the counsel and consent of the people, and considers not the good of the community, but the promotion of himself, his faction, and his household."

The second political principle that, according to the people of the time, made England a free monarchy was the existence of an ancient English constitution. This English constitution was not a written document like the future American constitution would be, but rather a collection of laws, decrees, and customs. It was perceived and experienced as an organic entity evolving with the accumulation of English life experience, while also relying on the ancient wisdom of Saxon law, which existed in early communities before the Norman conquest. All sides in England accepted the assumption that the primary concern of this ancient English constitution was the protection of the rights of the subjects. These rights were considered inalienable by any earthly authority—not even the English king—and were primarily the right to property and the protection of the subject’s liberty, summed up in the medieval adage "to the king the rule, to the subjects the property."

The belief was that the subjects’ rights aligned with the king’s privileges so that he would safeguard them. Under the Tudor monarchs, the integration of this dual tradition was maintained, but under Charles I, who saw himself as the representative of God and the sole authority responsible for enforcing divine will, the questions and concerns that had been the foundation of this constitutional tradition tore the political body into different factions.

Now let us return to the trial. After the reading of the indictment, the signal was given to the president of the court to demand the king’s response to the charges. The king's prosecutors, who had anticipated that the king’s convoluted oratory would betray him in a moment of distress, were stunned to hear his eloquent defense of his beliefs. “I wish to know,” the king began, speaking for the first time before the court, “by what power I have been called here, by what authority, I mean lawful authority. There are many unlawful powers in the world, thieves and robbers on the roadside. Remember, I am your king, your lawful king, and what sins you are bringing upon your heads, and the judgment of God upon this land; think well upon it before you proceed from one sin to a greater one… I have a trust committed to me by God, by ancient and lawful inheritance; I will not betray it to answer to a new and unlawful authority.”

From this initial stage to the end, the king’s trial resembled a game of cat and mouse, where those meant to function as the hunters were required to provide answers to the hunted. Thus, when Charles was asked by the court to respond to the indictment, the king sought to step back and scrutinize the legitimacy of the "play" he was forced to perform in. His response reflected his firm belief in his divine right, which had been imported from France at the end of the 17th century and aligned well with his authoritarian style of rule. In fact, the prosecution's situation was more problematic than the judges initially realized. If Charles’s accusers sought to have him answer for his crimes before Parliament, which was considered the representative of the English people, Charles refused to acknowledge the notion that a king owed any accountability to his subjects.

Four years after his coronation, in 1629, Charles dissolved that year’s Parliament and ruled without convening a new one for nearly 11 years—an unprecedented period, at least since the time of Henry VIII. Charles's prosecutors mistakenly viewed this step as part of his effort to establish a tyrannical regime. The American historian Robert Caro, who studied the nature of political power in modern America through the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, made the following claim: when a person is given unlimited power, all previous masks he or she wore are removed, revealing their true character and intentions. If there is any truth in this argument, then Charles’s personal rule serves as a fitting case study worth examining.

With the weakening of the campaign against Spain after Charles realized he would not secure funding from the Parliament of 1628, the Protestant king made a stunning reversal in his stance toward Spain and the Catholic camp. Now entering his thirties, the king showed an increasing attraction to two Catholic Baroque models: the courts of French and Spanish royalty and the renewed position of the Catholic Church following the Counter-Reformation. In a book of advice written by his father, James I, called Basilikon Doron (“The King’s Gift” in Latin), there is a piece of advice that Charles took to heart: “In your dress, be appropriate, clean, proper, and honest; wear it with effortless grace yet beautiful to behold, let it be between the toga of a judge and the coat of a general. Between the heaviness of one and the lightness of the other, thus marking that by your divine office you are mixed between two professions: the judge’s robe, as one who creates and expresses the law (divine); the general’s coat, by the power of the sword. For your office is a mix between the civil and the ecclesiastical paths.”

This advice reveals a key principle of the English Baroque: while Jesus sought to separate the two swords—the earthly and the heavenly—the monarchy in the English Baroque era aimed to bind them together, subordinating both to the king. However, the uniqueness of the English situation made it difficult for these Baroque ambitions to be realized. On one hand, a monarchy by divine right must be enforced through power and fear, as seen in the Spanish and French monarchies, where the Habsburgs and Bourbons maintained standing armies and generally obedient bureaucracies. On the other hand, the harmony and liberties of the English people—supposedly protected by the English constitution—created immense difficulty for the monarchy to become absolute.

Today, as in the past, the attempt to establish an absolute government tasked with preserving the liberty of the people is seen as absurd and contrary to common sense. The challenge of securing legitimacy for Charles's attempt at absolutism can also be seen reflected in the court culture of the 1630s, which portrayed an image of a besieged monarchy fighting off destructive external forces that sought to undermine the divine authority of the king. In a letter from Charles’s mentor, the Earl of Newcastle, written in 1628 when Charles was still a young and inexperienced king, the earl rebuked him for his puzzling distance from displays of power and theatrical grandeur in which the French and Spanish courts excelled.

“What protects you kings is above all the ceremony and royal splendor. The distance your people feel when they look upon you, the assembly of officers, royal heralds, drums, trumpets, grand carriages, and guards making way. I know these govern the people well, so that even the wisest among them cast off their wisdom out of fear of it.”

That said, it would be wrong to exaggerate Charles's difficulties in handling an early and softened version of absolutism. What likely eased the authoritarianism inherent in his character and political beliefs was not the king’s fear of himself or his near-unlimited power. While we know from his own testimony that Charles, like his father, sought to avoid the dangers of tyranny, which threatened to distort the institution of monarchy, this Aristotelian fear occupied the parliamentary camp far more than it did him. The king’s greatest fear can be summarized in one word: popularity. According to Aristotle, irresponsible monarchy deteriorates into tyranny, but the presence of irresponsible democratic elements leads to anarchy and demagoguery. The king’s fundamental belief was that all opposition to his royal will—and any sign of factionalism—was stirred up and maintained by demagogues who, by appealing to the base instincts of the lower classes, incited the people to resist the king’s benevolent will and overthrow the English free monarchy in the name of non-divine values like democracy.

Charles saw subversive and demagogic elements across all levels of his people and presented the divine hierarchy and order that his image represented as the remedy. This binary view helps explain why the many legitimate calls for reform from his subjects, expressed through Parliament from the 1620s onward, were interpreted as challenges to his legitimacy. The problem, as historian Robert Darnton demonstrates regarding a period a century later—France under Louis XV and XVI—was that public opinion in England gained increasing importance with the development and improvement of new distribution channels. Thus, the ability to spread and popularize new political ideas, scandalous gossip about the royal court, and news reports rapidly increased throughout the kingdom during his reign.

Charles’s greatest mistake likely stemmed from his political beliefs. He assumed that his loyal subjects clearly understood that God had entrusted him with the task of leadership, and therefore, they had an absolute duty to obey his commands. Meanwhile, the few bad subjects who opposed his will needed to be brought back in line by force. This belief explains his destructive insistence on not convening a new Parliament and his refusal to recognize that the regular functioning of Parliament and the passage of important decisions through it actually contributed to the harmony between the monarchy, the nobility, and the people, contrary to his views.

Using the two concepts we just explained—"the divine right of kings" and "popularity"—one can understand the complete and utter failure of communication that took place during the trial. After the king replied that he did not agree to recognize the court's authority, the president of the court, Bradshaw, responded in a political language opposite to that of Charles. Bradshaw called again for the king to respond to the indictment, this time "in the name of the English people, over whom you are an elected king." The king did not allow such a significant historical error to pass in silence. He gave an immediate response, emphasizing the contempt he felt toward such a democratic/popular declaration: "England has never been an elective monarchy, but a hereditary one for the past thousand years. I stand for the liberties of my people more than all those who pretend to be their judges."

On the second day of the trial, after having time to organize his thoughts on paper, the king even intensified his condemnation: "This trial represents a problem greater than my life because if power without law creates laws and thereby changes the fundamental laws of the kingdom, I do not know which subject in England can feel secure in their life or in anything they consider their own." By highlighting the court's illegal nature, the king attacked the subversive and arbitrary nature of the body that promoted the dangerous legal fiction of popular sovereignty. According to him, this democratic illusion would lead England to establish a regime that violates the laws of nature and God, which order the world according to a clear hierarchical structure, with authority flowing from the top down—from God to the king, and from the king to his subjects.

All this, of course, while the king himself was being accused of attempting to establish a tyranny—a degenerate, unholy, and arbitrary form of monarchy. From these difficult exchanges during the trial, the modern reader is exposed to the deep ideological polarization between the king and his judges—a polarization that caused every principled gesture by the king to be interpreted by his condemners as the arrogant refusal of a dangerous and unreliable man.

Thus, the trial, which was intended to last longer than the four days it did, was abruptly cut short due to the king's refusal to recognize the court's legal authority. Had the king responded to the charges and pleaded his innocence, his accusers lamented, it would have allowed witnesses to publicly present the king's actions, washing away all the sympathy and compassion that Charles's bleak situation aroused in his people. But once it became clear that this option was not forthcoming, the court abruptly ended the trial with the reading of the indictment on January 27th. And when the indictment was read, declaring that Charles Stuart was a tyrant, traitor, and murderer, the king was shocked to learn that his punishment was death by decapitation.

Once the verdict was announced throughout the kingdom, Charles's exiled son, the Prince of Wales, hurriedly sent Oliver Cromwell a blank sheet of paper, signed with his name, pleading with Cromwell to send back all his demands in a last-ditch attempt to save his father's life. No response was received. Three days later, on January 30th, two shirts were prepared for the king. Since the execution took place on a cold English winter day, the king worried that if he wore only one shirt and his body trembled from the cold, the crowd would mistake it for fear.

Around two o'clock in the afternoon, Charles was brought to the scaffold set up outside Whitehall Palace. After final words, in which he sought to explain that neither he nor the two houses of Parliament were responsible for the two civil wars—hinting at subversive forces that are to blame for all the calamities that had befallen England—the king wished to make clear, just as Jesus did on his final journey, that he forgave his executioners and asked God to grant them the same mercy, provided they would follow the right path for the sake of the kingdom and recognize his son as the rightful king.

His final words were: "I go from a corruptible crown to an incorruptible one, where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world." One of the crowd present, a 17-year-old boy, remembered until his last day the cry that erupted from the crowd when the axe fell: "Such a terrible cry I have never heard before, and I hope I will never hear again."

In conclusion, the trial of the king, along with the significant events that followed, reveal the uniqueness of the English Baroque. What appeared to Whig thought in the 17th and 18th centuries as an inevitable chain of events leading to the liberation of the English people in the name of classical republican values, has been reconsidered in recent decades as a political culture in crisis. This culture was driven by events and difficulties, responding to them with increasingly extreme measures rather than leading them with a coherent alternative ideology. If we compare the execution of Charles I with a more famous one—that of Louis XVI in 1793—we find a stark contrast. While Louis XVI was executed by decision of the French Republic, after the monarchy had been abolished and he was dethroned, Charles I, on the other hand, was tried and executed while still the King of England, officially by the House of Commons. Furthermore, it was Charles’s unprecedented death that necessitated the abolition of the monarchy, not the other way around. The republic that was established was, therefore, a result of the monarchy’s abolition, rather than an ideology that led to its downfall, as was the case in the French Revolution. Not only was Charles’s death conceived as an emergency measure, but even after the king's head was severed, it took weeks before the army leaders—the de facto rulers—had any clear idea of what the political order in a headless kingdom might look like.

The lessons learned from the events you survey remain in the Commonwealth of Virginia, along with its motto today, “Death Ever to Tyrants”

And then after a dose of Puritanism they made his son king. Unbroken monarchy ever since.