"In the Beginning": The Jewish Debate Over What Came First

The very ancient, endlessly fascinating debate on the question of what came first in the creation of the world

There is no real difficulty in proving that there is no such thing as a true "beginning" in human action or creativity. Every creation, deed, or statement builds upon a previous layer, woven into an unbreakable web of earlier and later. Johannes Gutenberg did not invent the printing press any more than the ancient Chinese did. The Wright brothers refined and improved upon earlier ideas in flight. This fact stands in direct contrast to divine acts, and from the very first verse of Genesis, the unique character of divine creation is marked with its own Hebrew word: bara—“creation.”

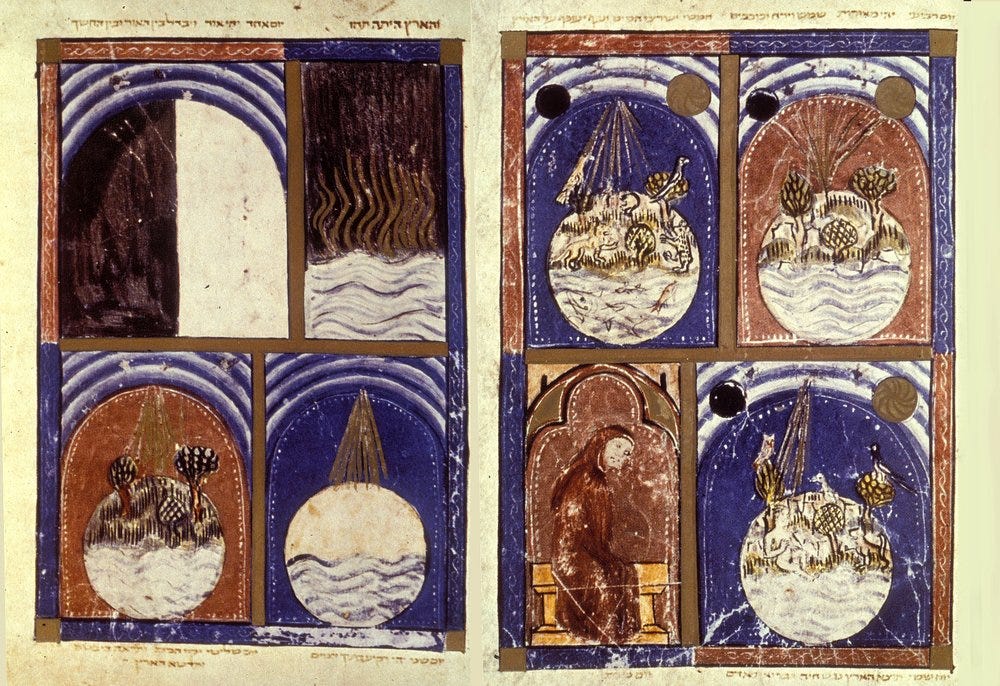

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was formless, and darkness hovered over the face of the deep, awaiting light—and later, eyes to witness this absolute novelty.

Even the sages of the Talmud disagreed on how to interpret this opening of Genesis. In chapter 2 of Tractate Hagigah in the Mishnah, we find a prohibition against engaging with Maaseh Bereshit (the work of Creation)—a code name for the act of creation prior to the creation of humankind:

One may not expound on sexual matters in groups of three,

nor on the work of Creation in groups of two,

nor on the work of the Chariot [Ezekiel’s vision] alone—

unless he is wise and understands of his own knowledge.

And immediately after:

Whoever looks into four things—it would have been better had he never been born:

What is above,

what is below,

what came before,

and what will come after.

And whoever does not honor his Creator’s glory—it would have been better had he never been born.

But anyone familiar with the heroes of the Talmud knows there is nothing the sages loved more than transgressing the very exegetical limits they themselves set. And so, in that same tractate and chapter, we find an extended discussion on the creation of the world—Maaseh Bereshit.

Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel, which forms the two (opposing) great traditions in Jewish law, debated the proper order of creation: were the heavens created before the earth, or the earth before the heavens? To resolve the contradiction between the verses "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth" and "On the day the Lord God made earth and heaven," each house turned to a third, decisive verse.

Beit Shammai, holding that the heavens came first, quoted from Isaiah:

"The heavens are My throne, and the earth is My footstool"—

just as a king first fashions a throne, and only afterward a footrest.

Beit Hillel, who believed the earth preceded the heavens, also turned to Isaiah:

"My hand laid the foundation of the earth, and My right hand spread out the heavens,"

and likened God to a king building a palace—starting from the foundations below before constructing the upper stories.

Other sages sought the very materials from which the world was shaped. They interpreted the term tohu va’vohu (formless and void)—which in the Bible describes the earth at the moment of its creation—as a primordial substance that predated the world and from which God shaped His creation. Unsurprisingly, this startling reading provoked discomfort among their opponents, who asked: how could the perfect God create the world from faulty matter?

Some sages, interpreting the phrase "and there was evening and there was morning" for each day of creation, proposed that many evenings and mornings preceded the first official day. In those lost times, they believed, God created and destroyed worlds—like an artist drafting sketches before arriving at the final, complete version.

How exactly did He do it? The Zohar, the most influential book of Kabballah, expresses this beautifully and succinctly:

Istakel be-oraita u-vra alma—He looked into the Torah and created the world.

To my mind, the most interesting interpretation comes from one of the greatest Babylonian sages, Rabbi Yehuda of the third century C.E. According to him, neither the heavens nor the earth were created first:

Rav Yehuda says: Light was created first.

It is like a king who wished to build a palace,

but the site was dark.

What did he do?

He lit torches and lanterns to see.

Rav Yehuda compares God to an architect wishing to build a palace, and so—before anything else—He lights a lamp. From this, Rabbi Yehuda concludes that light was not only one of the world's foundations, but likely the most basic among them.

Just as one lays a cornerstone, so light was created first.

After all, how can you build something you cannot see?

While intended in a secular vein, I've always liked the astrophysicist Sir Arthur Eddington's humble assessment, "It's not that the universe is stranger than you imagine, rather it's stranger than you can imagine". I usually pair that with Saint Augustine: "That which you know is not God. If you think you understand, you have failed".

My greatest comfort comes from the Rabbinical Iris Dement, who spoke with wisdom in Let the Mystery Be.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nlaoR5m4L80

We are light beings or, with the quantum physics in mind, quantum beings collapsing the wave function all the time without time, space and spacetime. We are creatures and we create so in a (human) sense(s) we are god🙏