When I was a child, I had a vivid and precise image of God—until I discovered what a 2,000-year-old Jewish Midrash says about divine appearances.

In my feverish imagination, God was an elderly but muscular man, adorned with a white beard and the side curls of an English judge. The upper half of his body, from the waist up, was entirely sky-blue (except for his beard and white hair), and his legs were made of cloud.

Where did this image come from? I don’t know.

Of course, Maimonides (1138–1204) would declare me worse than an idol-worshipper for daring to hold such a concrete image of God in my mind. But I take comfort in an idea that appears already in the Talmudic Midrash.

In the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael—a Talmudic legal Midrash on the book of Exodus from the 2nd or 3rd century CE—two revelations of God to the Israelites fleeing Egypt are described. It says, in the commentary on Exodus 20:2:

“For He appeared at the sea as a warrior making war, as it is said (Exodus 15:3) ‘The LORD is a man of war,’ and at Mount Sinai, as a compassionate elder, as it is said (Exodus 24:10) ‘They saw the God of Israel.’”

These two divine appearances are tailored exactly to the needs of a frightened, newly liberated people. When they need a warrior, God appears as one. When they need law and guidance, He appears as a merciful elder.

But—and in the same breath—the Midrash warns: these are both appearances of the same God. As it continues in that same passage:

“So that Israel would not give the nations of the world a pretext to say there are two powers. Rather, ‘I am the LORD your God’: I am the one at the sea, and I am the one on land. I am the one in the past, and I am the one in the future. I am in this world, and I am in the world to come!”

The Midrash’s message is clear: God reveals Himself in the form that we need—sometimes as a warrior, sometimes as a merciful elder, and sometimes, perhaps, even as a figure painted in sky blue and clouds.

But while God can choose to appear in whatever form He wishes—and, indeed, in whatever form we need—it is forbidden for us to depict Him in any physical shape. To give tangible form to the One who only allowed Moses, His beloved, and a chosen few that accompany him to see God’s back.

At Mount Sinai, Israel received the Torah, embodied in the Ten Commandments. The Second Commandment declares:

You shall have no other gods before Me. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

This dynamic appears again and again throughout the Bible. And it’s not usually about literal images of the God of Israel, but rather about the people's attraction to foreign worship. The biblical prophets often mock and sometimes shatter idols—an image that would later carry into the Quran, when Muhammad destroyed the idols in the sacred Kaaba.

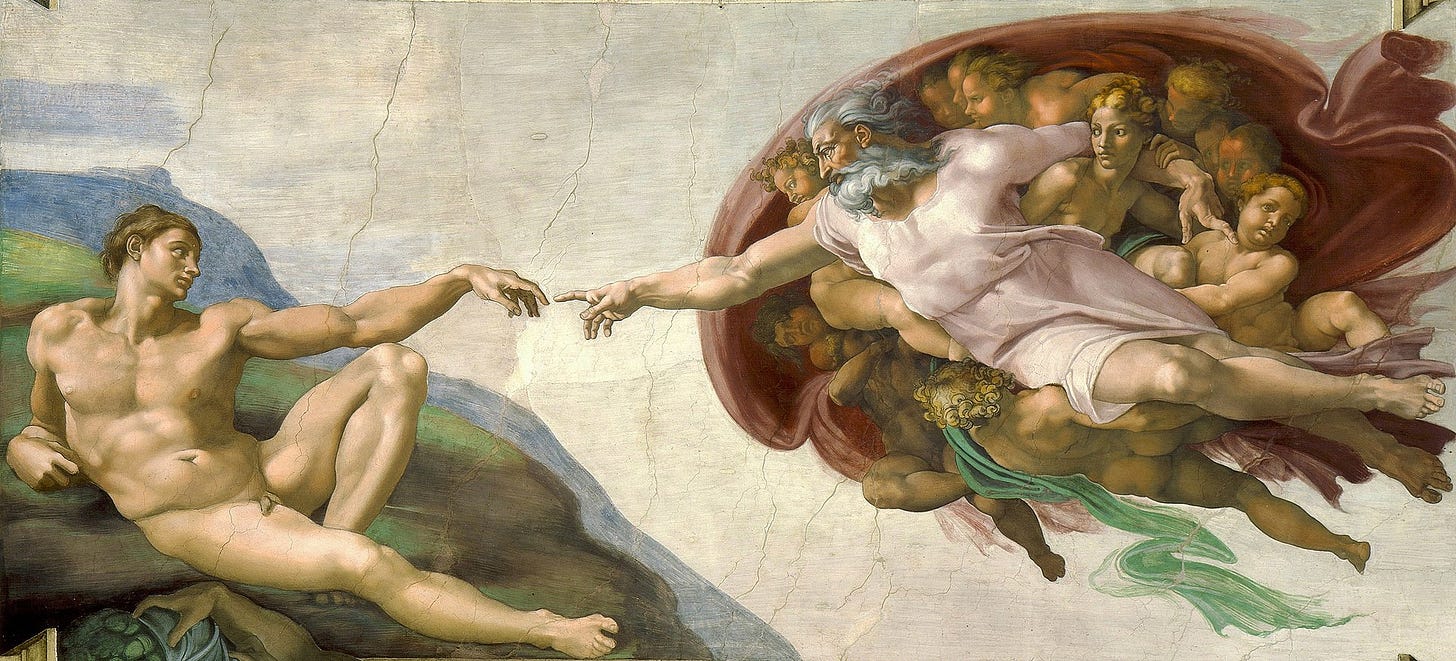

Christianity had less trouble with portraying God. But for Judaism, it’s difficult to imagine a work like the Sistine Chapel, where God’s curls glisten with morning dew. Jews found a different path. A wondrous, original one. They sculpted God through text. They painted the divine not with pigment and brush, but with words.

And that’s the case with the remarkable text Shiur Komah (a name that can be translated as Dimensions of the Body).

A Sensory Experience of God

Contrary to everything we’ve been taught about the Judeo-Christian—and certainly Islamic—God, the Bible does not shy away from the idea that God has a body or form. Even before the Sinai revelation, when Moses, his brother Aaron, and the seventy elders ascend the mountain, the biblical narrator says explicitly—twice in the same verse—that they saw God, with the Hebrew text actually using two distinct words for seeing:

“Then Moses went up with Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel.

They saw the God of Israel, and under His feet was something like a pavement of sapphire stone, as clear as the very heavens.

But God did not raise His hand against the leaders of the Israelites; they behold God, and they ate and drank.”

—Exodus 24:9–11

The text draws a sharp line between ordinary vision and elite revelation—the aristocracy of Israel sees God, then eats and drinks in His presence.

Philosophers like Maimonides would argue against a naïve reading of this verse. They would say, “The Torah speaks in the language of humans.” Just as “the land vomited them out” is a another bibilical metaphor, so too are descriptions of God’s body—which are perhaps “super-metaphorical”.

But the important thing, in my view, is that this argument adds complexity to something that seems quite simple. The text says clearly, and not once but twice: the elites see God. They behold Him. Then they sit down and eat—perhaps to emphasize the physical, bodily nature of the experience. This isn’t the later, abstract mysticism found in all three religions. It’s a visceral, sensory encounter with God.

Shiur Komah takes this mytho-theological logic to its extreme.

The book belongs to a corpus of early Jewish mystical literature called “Heikhalot and Merkavah” literature. These texts describe the ascent of various Talmudic sages to the heavenly realms and their encounters with God. In a previous piece, I wrote about Judaism’s first heretic, who also took part in such heavenly journeys.

But Shiur Komah is slightly different. It is entirely concerned with God’s body—His staggering measurements, His various parts, and the cryptic names assigned to each.

“Rabbi Ishmael said: I saw the King of Kings sitting upon a high and exalted throne, with His hosts standing to His right and left. The angel Sar ha-Panim, whose name is Metatron, said to me: his ankle is called Paskonit Paskin Atmon Higron Sigron Sarton Sanigron Mikon Sakom Setim Shakam Hakirin Na Dokirin Zina Raba Nantos Zantof Hekikm…”

(The opening lines of Shiur Komah. Don’t worry if you don’t understand the strings of letters—the scholars don’t either.)

What do we learn from these divine dimensions? Mainly, that God is enormous. Too big for the frail human mind to comprehend. That’s a recurring theme in Heikhalot and Merkavah literature expressed brilliantly with an overwhelming linguistic effect. In another work, Heikhalot Rabbati (the Major Halls), the singing of the angels standing before God is described like this:

The first voice—whoever hears it immediately suffers and collapses.

The second voice—whoever hears it is instantly led astray and never returns.

The third voice—whoever hears it, his skull is shattered, and his ribs pierced.

The fifth voice—whoever hears it melts like water, his spine broken at the joints, as it is said:

‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts…’ (Isaiah 6:3)

Repetition is not a common device in the Bible, so when the vision of God is repeated twice, it matters. In Heikhalot and Merkavah literature, repetition is now a central tool. It creates confusion. A sense of suffocation. Awe. You’re standing—reading—before something truly biblically awesome.

Why would Judaism need a book like Shiur Komah, which describes God’s body with such startling detail? It’s a provocative question, of course. First, because we don’t know—and likely never will—the precise circumstances of its creation. And second, because people often create from an inner need they can’t fully explain, even to themselves.

So perhaps a better question is: is this a way to glorify God's vastness—as if to say, the bigger He is, the more majestic? Surely, that's part of it.

But I suspect something more is at play here. One of the central motifs in Hekhalot and Merkavah literature is the desire of God Himself that His chosen creatures—those who have undergone a rigorous process of preparation, described in great (yet mysterious) detail in some of these texts—reach the Throne of Glory, pass through the royal veil, and behold the "King in His Palace."

Shiur Komah is the means by which these riders of the chariot—in this case, one of the heroes of this literature, Rabbi Ishmael—bear witness to what he have seen. In a tradition where sculpting an image of the divine was forbidden, these mystics did something bolder: they stretched language to its limits, not to reduce God to human form—but to remind us that God’s true form breaks the human mind.

Well done - as I read, the thought occurred that moving away from God as static image opens a door to other faiths, including Hinduism - a complex structure of faith that many in the Western Hemisphere mis-take as mere idol worship.

I also reflected on the word “image” in relation to our own shifting appearance - and psyche -through a day, a year- decades. And sometimes - we make others into images we need at the time.

This discussion of images feels to be, at once, both quintessentially God-like, and so very human.

I love the idea of some of the apophatic literature out there. But yes, it often breaks the brain.