Sing, Goddess!

The Muse Was There All Along

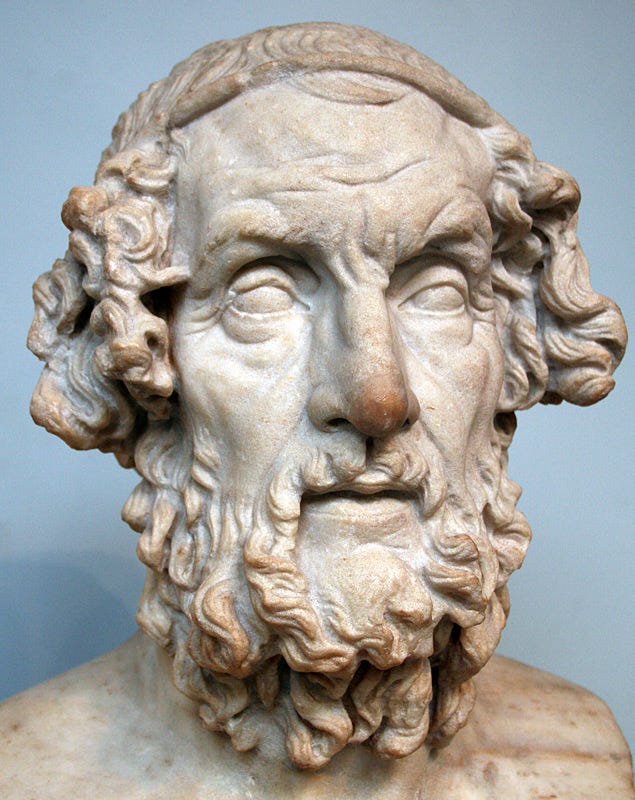

Some poets wait for the Muse to strike. Others, the truly great ones, simply let her break forth and sing through their throats. And this, of course, brings us to Homer.

These are the opening lines of what is usually talked about as the first literary work of the west:

Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath of Peleus' son Achilles, which caused the Greeks immeasurable pain and sent so many noble souls of heroes to Hades, and made men the spoils of dogs, a banquet for the birds, and so the plan of Zeus unfolded

We’re going to hear about the wrath, the main and constant theme of the poem, but not without the muse. It is she who sings, or make the poet sing. This is her song in a way.

In calling upon the Muse to speak through him, the mysterious and quite possibly fictional poet we know as Homer actually created a new literary convention (quite possibly the first one): the invocation of the Muse. From that moment on, all who followed in the epic tradition, and countless other poets besides, would turn to the Muse, asking and pleading for her grace. This convention would also allow for subtle, witty variations by later poets.

Virgil, the Roman master, began his Aeneid not with a plea but with a declaration:

“I sing of arms and the man, who first from Troy’s shores came to Lavinium…”

Only seven lines later does Virgil ask the Muse to recount the causes of Aeneas’s trials. He addresses her less as a goddess to supplicate and more as one to be instructed: this is how it will be.

Dante Alighieri, writing more than a thousand years later in the period we retrospectively call the Middle Ages, never actually read Homer. No complete or trustworthy Latin translation existed in his time. Even if he knew of Homer’s invocation, it is doubtful he would have used it. For much like his roman predecessor, Dante was a genius jealous of his own reputation.

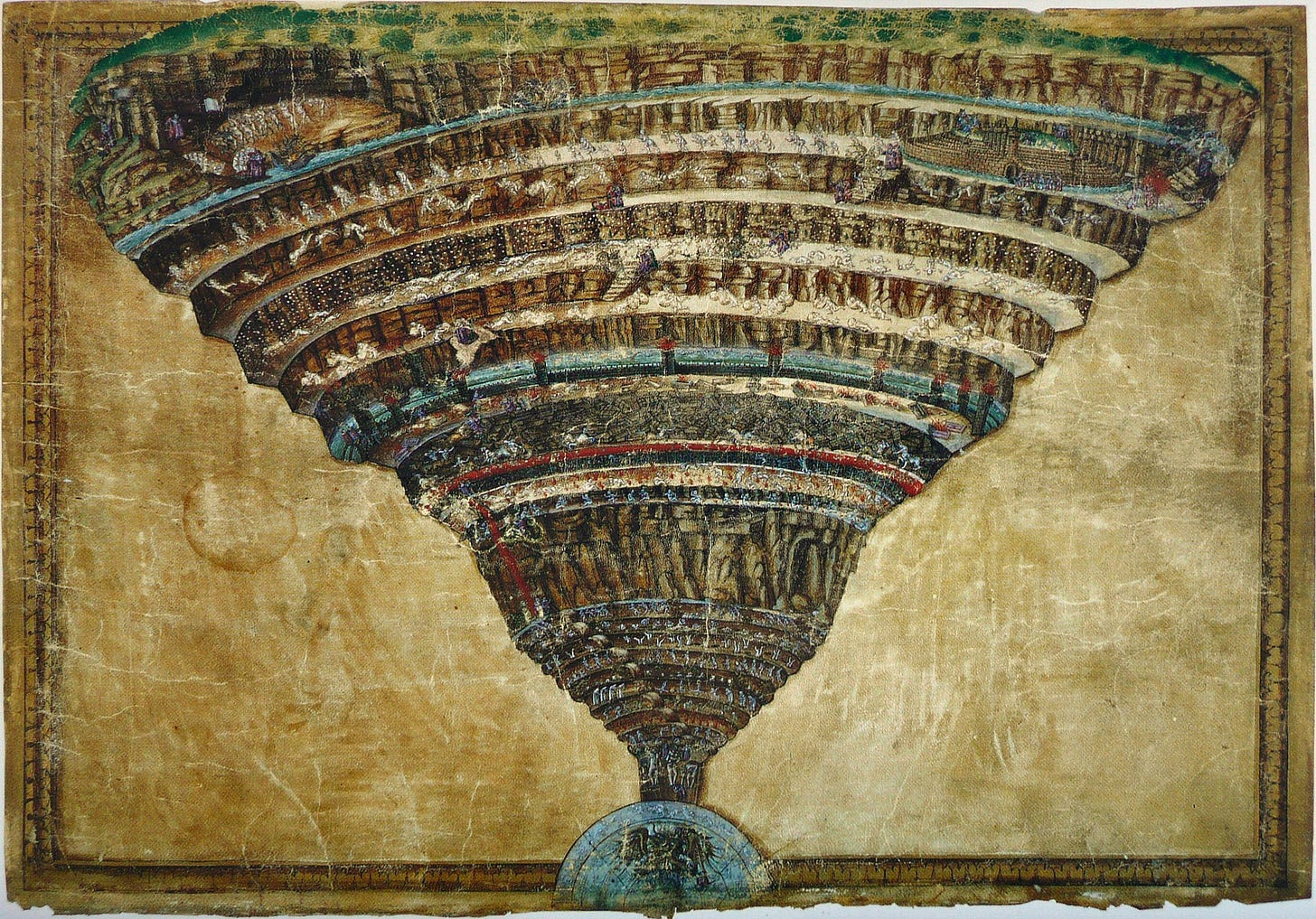

In The Divine Comedy he chose not to summon a Muse at all, but to appoint Virgil himself as guide, Virgil was not a muse exactly, no longer an inspirer of poetry, but a companion in spirit who leads the more modern poet through half the journey, from Hell to the heights of Purgatory. The rest, Dante entrusts to Beatrice, his beloved, who carries him into Paradise.

Strikingly, throughout the work Dante never meets the Greek gods. He does meet some of their monsters, several of their greatest heroes, and a gallery of historical figures. Among the persons he meets, assuming for a moment that he was a historical person, Homer himself. Dante places the fabled Greek poet in the first circle of Hell: a luminous, verdant garden, lit not by divine light but by a pale, artificial glow. This is where the great philosophers of Greece and Rome debate endlessly. Among them sits the poet who gave us The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Milton, the last poet in this lineage, lived, like Dante, in the Christian age. And at least in my eyes, his invocation of the muse was the most moving. He did call on a Muse to lead him in his poetic endeavour, but not the traditional Greek one. Nor did he ask her for beautiful images, resounding verses, or inspired lines, and certainly not to speak through his mouth. What the blind poet asked for was sight.

In Greek antiquity, the nine Muses were believed to be the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory—an origin that already reveals much about ancient conceptions of knowledge. Milton, however, turns to Urania, who was once the Muse of astronomy, but in his Christian context had come to be associated with the Holy Spirit. She is not the Muse of epic or music, to whom Homer and Virgil had turned, but of the heavens. An apt and interesting choice, since Milton’s subject is Heaven, Earth, and the depths of Hell. There is also, perhaps, a nod to the emerging modern sciences of his time.

In the opening lines of Paradise Lost, Milton asks this Muse to sing “of man’s first disobedience,” culminating in “loss of Eden.” Though we never hear the Muse’s reply, the poem’s very existence serves Milton (and perhaps us) as proof that she did answer. Immediately, she turns his gaze to the being responsible for humanity’s fall from Paradise: the serpent of Hell, Satan himself.

Here is vision indeed: a glimpse behind the veil of creation, prophecy in reverse. And with it, Milton seeks “to justify the ways of God to men.”

So, must every epic begin with a Muse? Dante gave us little more than an echo. And in other traditions, equally fierce and fascinating, there is no trace of such a device.

Beowulf, the great Old English epic, mentions no Muse at all. Its anonymous poet simply sings. For him, legitimacy comes not from divine inspiration but from the very act of storytelling: the oral passing-down from father to son, warrior to court-poet. In this way, Beowulf reminds us of another truth: that not every epic needs a Muse to soar. Sometimes, the poet himself, and the community that listens, is all it takes to seal a work’s fate, whether in immortality or in oblivion.

Beautiful description indeed and interesting comparative reflection Thank you Chen !!