The Jewish Scholar Who Was Desperate to Understand Kantian Philosophy

When, in 1768, 16-year-old Shlomo ben Yehoshua decided to stop praying, he had no idea where this decision would eventually lead him

The Library of Babel is an email newsletter exploring the wonders of literature, history and magic. All the installments are free. Sign up here:

After a long deliberation and intense pangs of conscience, Moshe Lapidot and Shlomo ben Yehoshua decided in 1768 to stop praying. Although the two close friends were only sixteen years old, they had already started families and found work as Torah teachers in their Lithuanian community.

Very quickly, they began to develop conflicting emotions: they feared that their actions were turning their backs on the faith of their ancestors, while at the same time, they enjoyed a sense of superiority sparked by their bold act. Whenever Moshe Lapidot was gripped by fear that the two were committing a sin punishable by severe heavenly judgment, Shlomo ben Yehoshua would reassure him, explaining that prayer is only one of the practices through which a person can serve God. He would go on to add that, in fact, it is a practice suited for the "ignorant masses" of humanity. Noble philosophers, he continued to inspire his friend, experience God through theoretical thought and intellect. The more Shlomo ben Yehoshua spoke on the subject, the more Moshe Lapidot became convinced of the righteousness of their actions.

Of course, the two young men still had families to support, a fact that prevented any possibility of openly rebelling against the closed Lithuanian-Polish society to which they belonged.

Here is where the story of the two could have ended: in an act of rebellion that held great meaning for them, yet remained completely hidden from their conservative community. However, one of those boys, the more determined and educated of the two, decided to venture thousands of kilometers away from Lithuania in search of himself. Over time, he left his isolated community and set off to wander across Europe. Along the way, he tried his luck with the emerging Hasidic movement, but, much like his encounter with Rabbinic Judaism, it filled him with disgust. In a moment of existential despair, he even attempted to convert to Christianity. Yet the Protestant pastor, who was impressed by the young man, refused to grant such a strange request from a Jewish youth who declared that he didn’t believe in the core tenets of Christianity, but merely saw it as a more moral religion than Judaism.

As his journey continued, on German soil, he came under the mentorship of a leading figure of the Jewish Enlightenment movement – Moses Mendelssohn. After teaching himself perfect German, he used Mendelssohn's connections to secure employment. He continued to delve into the writings of Maimonides (as a tribute to his greatness, he changed his name to Solomon Maimon), and over the years, he also developed an interest in non-Jewish philosophy. After mastering the teachings of Spinoza, Leibniz, and Hume, he felt compelled to study The Critique of Pure Reason, the book of the Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant, whose greatness he had heard much about.

The moment Solomon Maimon opened Kant's hefty volume, he discovered a timeless truth familiar to every eager young philosophy student – reading Kant is no simple task. This is how Maimon described his first encounter with the work:

"My approach to studying this work was most peculiar. Upon my first reading, I could grasp none of its sections, save for some vague understanding. I then strove to clarify this understanding through my own reflection, attempting in this way to discern the author's intentions."

As he continued reading, Maimon discovered that Kantian philosophy actually sharpened his previous conclusions, and he set out to write a book titled Transcendental Philosophy. This work eventually reached the hands of Immanuel Kant (Maimon was the one who put it there). Months passed without a response, and Maimon began to lose hope. Finally, Kant sent two letters: in the first, addressed to Maimon's old friend who had connected the Prussian philosopher with the eager Jewish thinker, Kant initially rebuked the friend, saying:

"But what possessed you, dear friend, to send me such a large bundle of exceedingly subtle inquiries—not just for reading, but also for study? I am, after all, in my sixty-sixth year of life, burdened with much work to complete my program... and besides, I am constantly occupied with numerous letters, demanding special explanations on various points of my system, and to add to this, my health has deteriorated. Therefore, I almost decided to return the manuscript with an apology, based on the reasons mentioned above."

And yet, something made him change his mind:

"However, I glanced at the manuscript, and immediately recognized its outstanding merit. Not only did none of my critics understand my ideas and the central question I posed as well as Mr. Maimon did, but only a few have shown such intellectual sharpness for such deep inquiries as these..."

In the second letter, addressed to Maimon himself, Kant congratulated him, stating that from his book, "a truly uncommon talent for profound sciences is evident."

It would not be an exaggeration to say that from this moment on, the name of the wandering Jew became increasingly renowned throughout Europe as a sharp critic and thinker. He continued to publish his writings in a long series of important newspapers (both Jewish and non-Jewish), and after the death of Moses Mendelssohn, he played a significant role in the flourishing Jewish Enlightenment movement.

When the young Shlomo ben Yehoshua decided, sometime in the mid-18th century, to stop praying, he was essentially deciding to embody the Enlightenment of the great philosopher Immanuel Kant. According to Kant, immaturity is expressed as "a person's inability to use their own reason without the guidance of another," and young Ben Yehoshua decided to use his own intellect. The fact that he was considered by many to be a Torah prodigy, with others already envisioning him growing into a great scholar and teacher, did not stop him from seeking another path.

Although young Shlomo ben Yehoshua had never heard of Kant while growing up in the closed Jewish community of the town of Nesvizh, his rebellious act eventually led him to leave the isolated Jewish community and embark on a journey thousands of kilometers away from Lithuania in search of his own path.

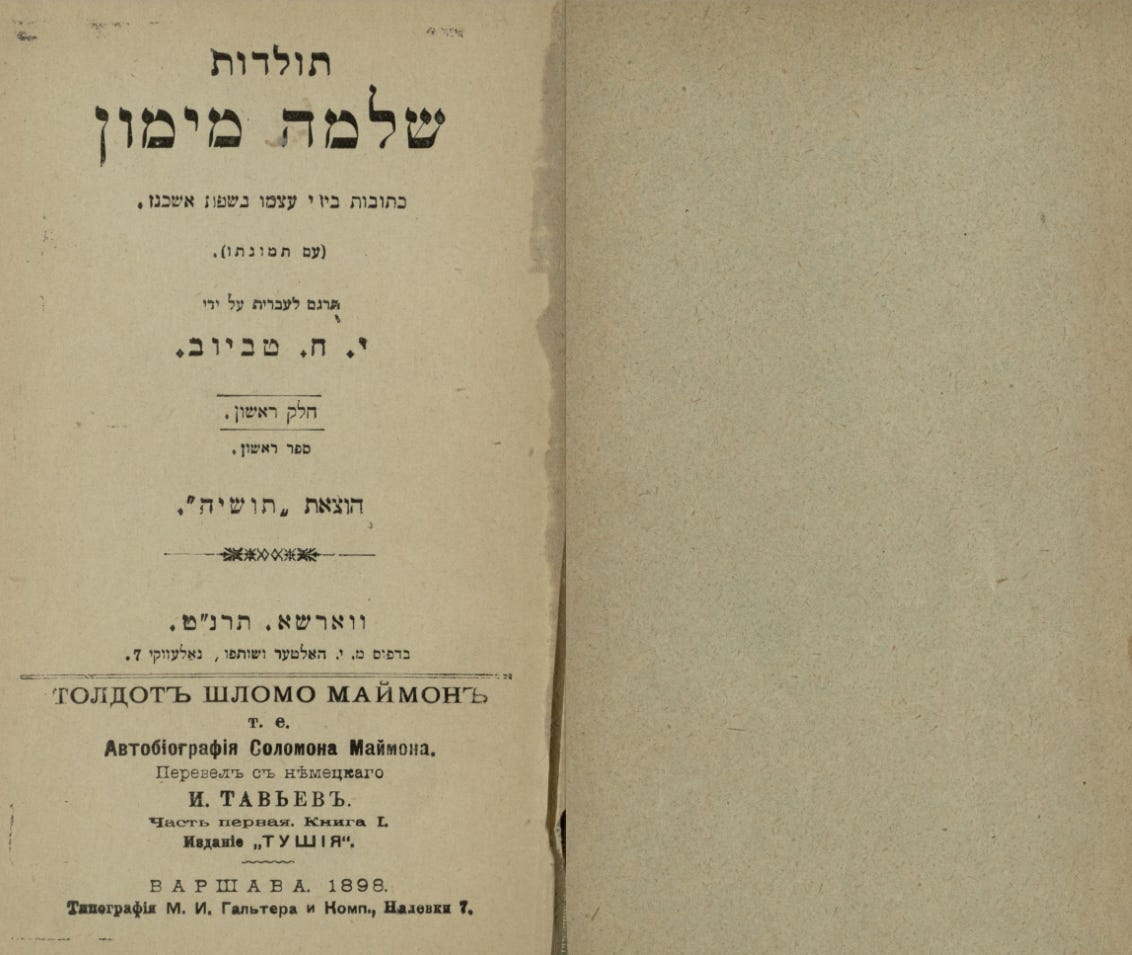

Solomon Maimon passed away at the age of 46 in Silesia, Germany. It is said that the children of the Jewish community where he was buried accompanied his final rest with a relentless shower of stones. Today, we remember him primarily for the autobiography he wrote, which provides an almost unprecedented glimpse into the tragicomic life of an 18th-century Jew who sought (and succeeded) to live among the great philosophers of his time.

Thanks for this. I had read about Maimon in Amos Elon's marvelous book The Pity of it All. He impressed not only Kant but also Schiller and Goethe, who wanted Maimon to move to Weimar and join his inner circle.

Astonishing documentation. Very interesting indeed Thank you Chen